Anubis, the Egyptian god of death and protector, was often depicted as a black canine or jackal. He served as both a protector of embalming as well as a guide after death.

Ammit served as the Keeper of Scales, weighing the heart of each deceased against Ma’at’s Feather of Truth to ascertain whether their soul would ascend to heaven or perish at Ammit’s mouth.

He was a god of death.

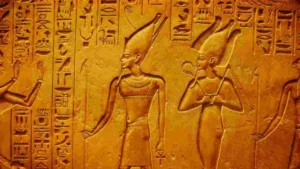

Ancient Egyptians held that death was an essential aspect of life. Egyptians believed that souls did not last eternally and could return. Anubis, the Egyptian god of death and protector of tombs, was central to this belief system and played three distinct roles during mummification processes: embalming bodies, guiding souls and protecting tombs from animals that may dig and consume corpses. He was even worshipped as a patron by embalmers and mortuary priests – wearing masks with Anubis’ face during mummification processes as a form of paying their respects while protecting tombs against animals that might dig in search of their precious flesh reserves! Unlike his counterpart, Anubis also played another significant role – with its three roles being embalming bodies, guiding souls into another dimension while protecting tombs from animals digging and eating flesh from intruders!

As part of Osiris’ myth, Anubis assisted Isis in embalming her deceased husband after Set had killed him, becoming known as the funerary god Anubis and becoming associated with embalming. Egyptians practised embalming to preserve their bodies before burial in tombs for burial under Anubis’ watchful eyes; his protective role extended even into protecting tombs where Egyptians would bury their dead mummies. Later times saw other gods emerge to sublimate Anubis as the god of the dead; nevertheless, he maintained connections to both places while remaining an immensely popular deity within funerary art.

Anubis was also revered as the god who guided souls to the afterlife, an integral role since Egyptians believed Ma’at (or Order and Balance) represented order and balance after death. A heart-weighing ritual was part of this ceremony. If it weighed more than Ma’at’s feather of truth (known as Ma’at’s “feather”), it could be devoured by Ammit (a hybrid god), while if equal or less than Ma’at’s feather it would pass to an eternal and blissful existence after death.

Anubis was often depicted at burial sites and funerary paintings as the guardian of tombs, often as half jackal/half human figures carrying divine sceptres or his iconic signature image, blood-splattered black/white oxhide hanging on poles from burials; at other times represented as dogs or snakes.

He was a god of mummification.

Anubis was the Egyptian god of mummification, cemeteries and afterlife. He appeared on funerary papyri as an object of protection for tombs. He served both physically and spiritually against grave robbers as well as malovent forces threatening death. His cult flourished throughout the Early Dynastic Period and the Old Kingdom before Osiris gradually took on many of Anubis’ duties.

Anubis was the Egyptian god of mummification and presided over all funerary rituals related to mummification, including embalming and mummy preparation. According to early Egyptian beliefs, only Anubis could reassemble bodies and prepare them for burial, with his companionship, including his trusty companion dog, serving as a guard during this mummification process.

Anubis’ presence was critical at the opening of a mummy’s mouth, using his “was” sceptre as a symbol of power and authority used by both Egyptian deities and pharaohs alike – it later served as a sign of royal rank as well.

Anubis was also responsible for awakening the souls of those being mummified during this process; he would appear near their mummies and awaken their spirit’s ka before leading them towards their final resting place. Additionally, Anubis would balance out a heart’s weight against that of Maat (truth); should this process tip favour the heart, it would be devoured by Ammit (an ancient Egyptian term for death goddess).

Anubis’ symbolism has long been one of the defining features of Egyptian art, appearing on many wall paintings and reliefs and sarcophagi, amulets, statues and prayers carved into tombs.

He was a god of the afterlife.

Anubis was the ancient Egyptian god of the afterlife and was responsible for leading souls into and out of the underworld. Additionally, Anubis played an essential part in funerary cults, developing embalming procedures as part of his role. Anubis also protected tombs against wild dogs and jackals, which would feed upon corpses to consume their flesh; to combat this issue, mummification was developed – this process preserved bodies using chemicals while they remained wrapped up with linen for further preservation.

Anubis was commonly depicted as either a jackal or a dog, although many Egyptians considered him both. His cult developed because it helped protect bodies from wild canines; Egyptians considered Anubis the ultimate guardian of their dead and would pray to him and put his statues on tomb walls in gratitude.

Anubis’ choice of the jackal as his symbol was no accident: this animal was ubiquitous throughout Egypt’s desert regions where many tombs and burial sites could be found, and was celebrated for its cunning and resourcefulness – qualities attributed to him when leading souls safely through the treacherous underworld.

Anubis’ duties as the god of the afterlife included weighing each person’s heart against a feather belonging to Ma’at, the goddess of truth and balance. If the heart weighed lighter than Ma’at’s feather, this meant they had entered into the afterlife through Duat; otherwise, it indicated they had committed sins that prevented their entrance; these hearts would then be devoured by Ammit, goddess of vengeance.

Anubis was first depicted as a full-bodied dog or jackal with pointy ears, represented as black to symbolize death and decay of human bodies. Anubis served as a protector for embalmers, so he was often featured alongside them in funerary art. Later, he would join Hermes, the Greek god of travel and transportation, to become their guide into the netherworld.

He was a god of jackals.

Ancient Egyptians considered jackals the guardians of cemeteries and necropoleis, though their actions often desecrated graves by eating dead bodies. Because of this, the Egyptians created Anubis as the most widely recognized god of death in their mythology; he also protected tombs during mummification rituals.

As soon as someone died, their body would be placed into a coffin and mummified before priests performed rituals to prepare it for its journey into the afterlife – purification, sensing, anointing – as well as use incantations to awaken its spirit, otherwise known as its “ka.”

After the mummy was complete, Anubis would awaken its ka. This step was essential as it allowed a deceased soul to enter the afterlife; Wepwawet assisted Anubis with this ritual. Anubis served as Guardian of Scales and decided the fate of individual souls by weighing their hearts against a feather representing Ma’at or truth; if their hearts outweighed Ma’at or truth, Ammit – commonly referred to by Egyptians as the “Devourer of Dead”, would devour them; otherwise, they would pass into heaven where Osiris await for continued afterlife life after death.

Osiris eventually overtook Anubis as the god of death and renewal; his role has since been more ceremonial and symbolic.

Artworks of Anubis often portray him as a black canine with erect ears, symbolising death and fertile soil for Egyptians. Additionally, pointed ears highlight his status as an unusual hybrid species between dog and jackal.

According to some scholars, it is believed that the god of jackals was inspired by an actual animal, specifically a type of dog known as a scavenger that preyed upon bodies left lying at ancient Egyptian graveyards for food. Egyptians associated the god of jackals with afterlife rituals and mummification ceremonies.