Rome emerged as one of the main forces shaping European civilization during its first millennium of existence.

Romulus and Remus, twin brothers rescued from drowning in the Tiber by a she-wolf, founded Rome. At first, they established it as a republic; however, power quickly became concentrated within an emperor’s grasp.

The Origins of Rome

Modern historians now recognize that Rome’s early development as a city-state and empire was not planned in advance; rather, it evolved as it came into contact with and conquered surrounding city-states, kingdoms, and empires. Each new territory needed to be integrated into Roman society while at the same time respecting their customs and traditions.

Rome attracted both Etruscans and Greeks, both of whom appreciated its form of government with its Senate and popular assemblies that enabled political participation by all freeborn men. Greek culture contributed greatly to the expansion of Roman culture, with Romans adopting advanced art, philosophy, and religion from these regions.

Rome was never an easy city to build; from its inception, civil wars and battles left Roman coffers empty, ultimately leading to real political power being concentrated among a small group of patrician and wealthy plebeian families whose leadership swiftly responded to crises while simultaneously creating an atmosphere of political instability and violence.

Roman victory at Veii resulted in victory but also brought with it an intense famine and grain shortage, prompting reformers led by Gaius Gracchus and Tiberius Gracchus to attempt to improve a lot of ordinary Romans by reducing tax burdens and widening access to public lands – however, these efforts failed dramatically, highlighting Rome’s deeply divided society.

Marcus Aurelius’ Empire reached its pinnacle under his rule between 161 and 180, comprising about one-quarter of the world’s population and boasting an extensive trade route network spanning Africa to Asia. However, its military might have begun deteriorating, with frequent wars draining imperial coffers while oppressive taxes increased wealth disparity within it.

Emperors also saw an increase in centralized power, most noticeably under Augustus (r. 27 BC-14 AD), who instituted reforms that reduced bureaucracy while simultaneously shrinking his army size and instituted censuses that provided accurate population figures.

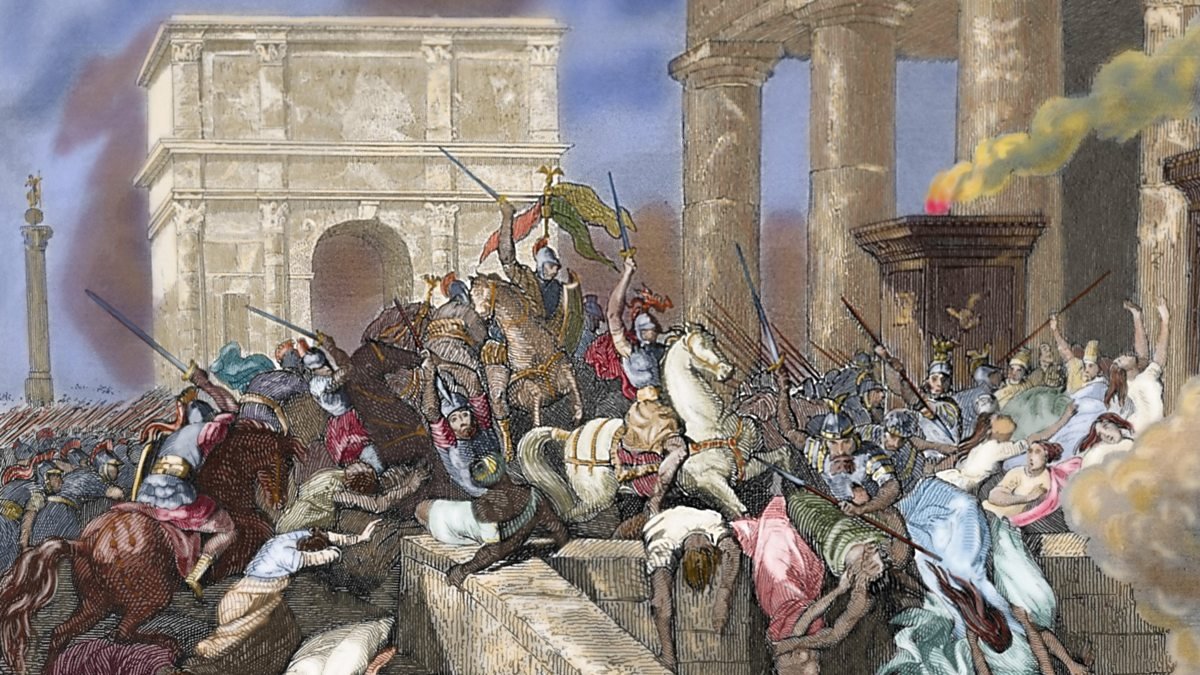

The Fall of the Empire

The Roman Empire was one of the greatest powers in ancient history. Spanning over much of Europe and northern Africa, its influence extended across both military and cultural fields – boasting an army of disciplined soldiers, an efficient bureaucracy, talented craftspeople, advanced law systems and brilliant city planners, not to mention an expansive culture which included contributions from other ancient peoples.

Underneath all this accomplishment, however, the empire was undermined by domestic and internal issues that ultimately caused its downfall. Rome’s large size caused a strain on the social fabric of Rome, creating bitter rivalries among its elite as well as widening the gap between rich and poor.

First and foremost, among Rome’s obstacles was a chronic labour shortage. Rome’s agrarian economy relied on slave labourers to cultivate fields and work as craftsmen. Rome’s constant expansion fed into an engine that kept this engine going; when this engine stopped running, so did the supply of slaves dwindle.

This labour crisis was compounded by other economic and social challenges which had long plagued the republic. Harsh taxation and inflation had an adverse impact on imperial finances. Excessive military expenditure straining state finances resulted in civil wars where generals vied for power.

Gaius Marius, an ordinary Roman whose military skill led to him being promoted as consul in 113 B.C., set into motion the cycle of warlords that would come to dominate Roman society over the coming years. General Sulla emerged as a military dictator around 82 B.C., while his heir Pompey served five times as consul.

At the time Augustus came to power in 27 BC, Rome had effectively degenerated into a feudal state governed by a princeps, or first among equals. Augustus established himself as chief by decreasing senatorial class influence while simultaneously increasing that of equestrians; additionally, he formed a standing army of 28 legions directly under his control and ended the ancient republican tradition of rotating consulships.

Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, who followed, were relatively benign emperors, but their rule contributed to a slow but gradual decline of the empire. By the fourth century AD, Rome’s capital city, Nicomedia (later Byzantium), had begun shifting east.

Conclusions

As Rome prospered, its borders expanded and eventually encompassed much of the Mediterranean basin, western Europe and North Africa. Rome quickly established an impressive empire featuring gifted leadership, brilliant tactics and impressive innovation across warfare, statecraft, city building and laws – while accepting and adapting aspects from other ancient peoples, such as the Greeks, while maintaining their own culture.

Political offices and institutions had developed during the republic to prevent any individual from becoming too powerful, yet these began to unravel with empire expansion. Julius Caesar conquered Celtic Gaul for Rome to expand beyond Italy for the first time ever; when his assassination occurred in 44 BC, his heir Octavian took control and became the first emperor, but subsequent Julio-Claudian Dynasty rulers did not match their predecessor’s strength or vision, gradually weakening Rome’s grip on a world it had conquered so easily.

In the fourth century, an array of military and financial disasters struck Rome hard. Invasions, usurpations and political dissension sapped resources while harsh taxation, inflation and extortion from stationed troops all combined to cause widespread economic misery – creating a vicious cycle as economic instability undermined military strength, leading it to spend ever more on maintaining its strength while draining off more money from its treasury resulting in further corruption by corrupt officials or small-time thieves.

Further undermining support for the empire was Christianity, which diverted wealth away from state affairs to church affairs. Clerics preached doctrines of patience and pusillanimity while any remaining remnants of the Roman spirit fled into monasteries where they could plead their virtue of abstinence and chastity.

At its height, Rome was in chaos as a result of Emperor Commodus’ abuse of power and inability to control his soldiers, leading them into civil war among general populations before grain shortages revealed their treachery to Commodus, leading him to murder his sister.